If someone were to ask me to critically appraise the scientific merits of a study arguing that birth control usage caused earthquakes by changing the mating behaviors of fish, I might have had an easier time than I did with Dr. Theresa Deisher’s widely shared study. That may be over the top, but it is kind of true. In such a scenario, I would have been able to say to myself, like most other people in the scientific blogosphere are doing with the Deisher study, “This is just too absurd, too poorly done to waste any more time refuting it!” But, I can’t do that because you, my brothers and sisters in Christ, deserve to know how badly you are being deceived by a study that is so abominable, it would be an insult to bad science to call it bad science.

This post is very thorough and a bit intense. I’ve been informed that it may be a bit much for the average layman. Feel free to jump to the summary of conclusions.

This will be a multi-part series (so hold your questions and don’t expect comments to be approved until the end, please) because I want to do justice to just how much scientific fraud exists in this study…

Linear regression and Change points— You can’t just do that!

As a rule of thumb, any time I see the words “linear regression” in a paper that makes novel, extraordinary claims, my red flag for pseudoscience goes up. The reason is that linear regression, especially Deisher’s simple linear regression, will show how well a (presumed) predictor variable and response variable correlate to each other. The keyword there is correlate. In order to make conclusions about what or whether something caused the correlation, far more analysis must be made and assumptions and criteria met. But the problems with the study start before we can even start that conversation.

Deisher’s analysis centers on the idea that a linear regression model between birth year and diagnosis of autistic disorder (AD) encounters “change points” and that these change points correspond to changes in exposure to vaccines cultured in fetal cell lines and cannot be explained by other variables.

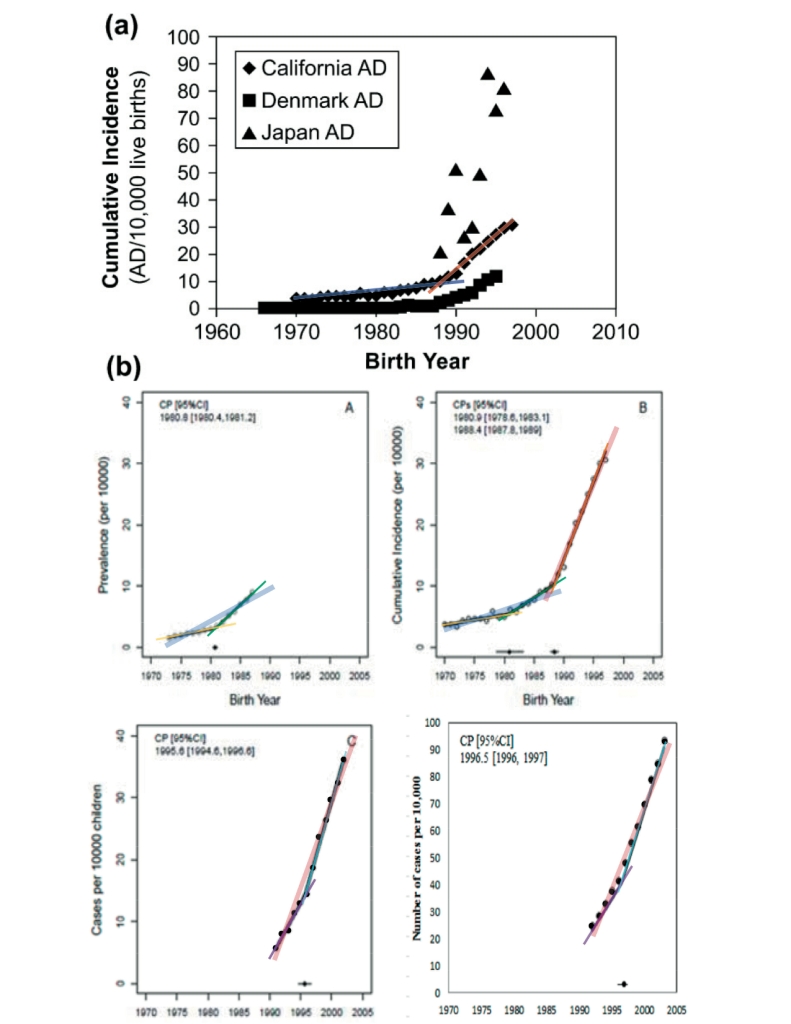

The first problem is that it is highly doubtful that these change points even exist for the data. That is not to say that a change point could not exist; in fact, McDonald and Paul, whose 2010 paper Deisher cites, used the exact same data from California and found a single change point:1987.5. Just eyeballing the data, this seems reasonable; there is a very low slope from 1970 until we start approaching 1990 and then AD diagnoses skyrocket. Yet, Deisher claims that there were two change points—1980.9 and 1988.4 in the CA data. What was the rationale? “2 change points…resulted in a better fit of the data”.

Yes, Captain Picard, you’re right. You can’t just do that. With any data set, if the points are not perfectly linear, you can always get a “better fit” if you partition the data (i.e. make a change point). That does not mean that it is valid to do so. You could add three change points and get an even better fit, all the way up until there is a “change point” between every single data point. What would make a change point valid and significant? Let’s look to McDonald and Paul: “In the California study… the calculated changepoint year was determined to be significant because the pre- changepoint regression slope in each case was significantly different from its respective postchangepoint regression slope”

For the CA sample, the slope went from 0.24-0.37 to 2.3-2.5 around the single change point of 1987.5, roughly a 6 to 10 fold increase. But it is obvious, even visually, that there is nothing remotely close to the same change occuring between Deisher’s “change point” of 1980.9, nor around her change point of 1980.8 for the US Department of Education Data. Looking at a newsletter from April 2010, which uses the same data sets (never mind the typo regarding the start dates; the graph shows that they are the same), we see that the slope pre-1980 is 0.1829 and post-1980 is 0.712, not only a much smaller increase, but also hardly any deviation from the 0.24-0.37 slope for the whole line. Another thing to consider is that this was already a very small data set, just 28 points for the CA data, one for each year 1970-1997. To validly partition it just once would require a huge change to account for the fact that you have reduced the number of points (thus, increasing your probability of error or spurious chance) used to make the regression lines. To do it more than once? “Ridiculous” even if we had great changes, which we obviously do not. That same problematic scenario occurs, only more so, with the “change point” of 1995.6 (On p. 273, it says the CP is 1996.5. However, only Fig. D has this change point; Fig. C, the 2010 NL,and the rest of the study have it as 1995.6.) Even fewer data points; even less perceptible change.

Bottom line: Deisher’s change points for the United States are clearly artifacts of a poor/invalid statistical approach.

Correcting historical errors when analyzing “change points” results in no correlation with fetal cell line vaccines

Even though Deisher’s change points are artificially forced into existence, I will operate from this point forward as if they are real… but keep in the back of your mind that they aren’t. The other thing to remember is that these change points are for year of birth, not simply the year.

Deisher makes some critical historical errors, some so glaringly obvious that I was so surprised that no one had ever mentioned it in the 5 years Deisher’s hypotheses have been on the radar that I had to check with several people to make sure I hadn’t had a stroke and lost my ability to read.

Central to Deisher’s claim is the idea that the change points— 1980.9, 1988.4, 1995.6— correspond to the “universally introduced environmental factor” of fetal contamination from WI-38/MRC-5 fetal cell lines used to produce vaccines. She cites the licensing of MeruvaxII (rubella) and MMRII in 1979; the addition of a second dose of MMRII; and the “approval and introduction” of Varivax.*

Here’s the thing, though. Other than the licensing of MeruvaxII and MMRII, those other two things did not happen prior to the “change points”! In other words, the slope had already started changing before the vaccine exposure changes so the vaccines could not be the cause of the change. A universal, 2-dose schedule for MMR was not recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the CDC body responsible for immunization schedule changes, until December 1989. Prior deviations from the 1-dose schedule were due to outbreak control or for areas of recurrent measles, which would apply to very few regions and few children. Therefore, a change point of 1988.4 cannot correspond to the second dose of MMR because the change was already occurring prior to its introduction! Put another way, the only one of Deisher’s change points that is even close to being valid has no correlation to fetal cell line vaccine changes.

In a similar, but less impressive way (since the change point was so unimpressive), the Varicella vaccine, Varivax, while licensed in March 1995, was not universally introduced to the vaccine schedule until 1996. Therefore, a change point of 1995.6 also would not correspond to Varivax because changes were occurring prior to the recommendation that all children get the vaccine.

“Ah,” but you say, “this data was for birth year, not simply the year!” Yes, I’m glad you remembered… and, yet, it continues to make Deisher’s claim at correlation even more unjustifiable.

While Deisher attempted to take the child’s age into account when looking at correlations between AD diagnoses and changes in diagnostic criteria, she made no such attempt with vaccination. With the vaccines, she suggests that introduction yields instant change in AD diagnoses.

I’ve already shown that this isn’t possible given when the recommendation changes historically occurred above. But let’s see if these change points correlate between when the birth year groups could actually have been exposed to the vaccines based on the schedule.

The licensure of MMRII in 1979 would mean that any child 15 months of age at that time could use MMRII to satisfy his measles vaccine requirement. The first birth year that this would affect in full is 1978. The 1989 recommendation for a 2-dose MMR schedule is a bit tricky; from 1989 to 1997, the second dose could be administered at 4-to-6-years-old or 11-to-12-years-old. The earliest birth year that this recommendation would affect is 1978 (12-years-old in 1990, since most children turning 12 in 1989 would have done so prior to the Dec. 1989 changes). The latest birth year would be 1986 (4-years-old in 1990). This is a major problem because if the introduction of the vaccines, whether by licensing or schedule, were correlated to change points, we would expect those change points to be for (or closely following) birth years 1978 and 1986. That did not happen in Deisher’s model.

Obviously, this is overly simplistic, which is one of the things that frustrate me so much. It cannot be and is not as simplistic as this study would make it out to be. But, in this section at least, operating on Deisher’s own assumptions, Deisher’s claim that introduction of fetal cell line vaccines correlated to change points in AD diagnoses is not justifiable.

Correlation between Deisher’s “change points” and Diagnostic changes

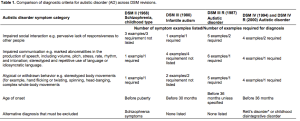

Before we can discuss the numbers, Deisher’s introduction to the section on the Diagnostics and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) changes is both bizarre and confusing. Bizarre because in Table 1 (see below), she divides the categories for autism diagnosis into three areas—social interaction, communication, activity/interest/behavior. These similar categories only exist between DSM-III-R(1987) and DSM-IV(1994), and then she forces the prior two DSMs to fit that mold to make the claim that “symptom categories are consistent across DSM revisions”, which is bizarre and erroneous.

Further, what she fails to take into account properly is the requirements for diagnosis. While it is true that both DSM-III-R and DSM-IV both required 2 examples of autistic social interaction, 1 example of communication, and 1 example of activity, that sum would not yield a diagnosis of autistic disorder. In DSM-III-R you needed 8 examples in total from those categories, but in DSM-IV you only needed 6. This is not more restrictive, it is, in fact, “less stringent.” Additionally, Table 1. incorrectly implies that DSM-III (1980) is least stringent when, in fact, it is the most stringent. To be diagnosed with Infantile Autism (the precursor to AD), the child needed to meet 5 criteria (lack of responsiveness, gross language deficits, peculiar or absent speech patterns, bizarre responses, absence of delusions) in addition to onset prior to 30 months. If any one of those very subjective criteria were missing, the child would not be diagnosed as autistic.

Compounding the issue further is subjectivity and language. If you read the diagnostic criteria yourself, anyone with any sense of language will note a general change when discussing diagnostic criteria. A 1989 report on the changes in criteria for autism between DSM-III and DSM-III-R described it as such: “There are major changes [emphasis mine] in the diagnosis of autism between DSM-III and DSM-III-R…. Subjective words such as ‘pervasive’, ‘gross deficits’, and ‘bizarre’, which may have made raters somewhat hesitant to use this diagnosis with older and higher functioning individuals have been removed.” An increase in autism diagnoses was expected and observed due to these “major changes” that, according to Deisher, do not exist. Other studies have also found that changes in diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV “were associated with higher case-finding rates than earlier criteria (DSM-III, DSM-III-R and ICD-9), resulting in approximately twofold higher reported estimates of prevalence….”

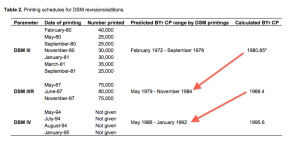

The cynic in me can’t help but think that this was not due to simple sloppiness or incompetence, but to purposefully obfuscate the fact that the DSM data do not do what Deisher claims. If we assume her methodology of calculating change point ranges for the DSM changes are valid (Table 2.), then her stated change points do, in fact, correlate to DSM changes! Change point 1980.9 (stated as 1980.85 in Table 2) does fall between May 1979 and Nov. 1984. Change point 1988.4 does fall between May 1986 and Jan. 1992.

Something further to consider: Deisher is using administrative data from government agencies, not clinical data. Researchers have highlighted many problems in using administrative data (Laidler 2005, Baxter, et. al. 2014), but there is one aspect that I want to focus on— underrepresentation. Very young children often have little or no interaction with government agencies until they are school age. Thus, those under the age of 5 to 6-years-old, will be very underrepresented in the data. So, when I looked at the correlation between DSM changes and birth year, I thought of what might be the scenario for an on-the-ball psychologist with a child from the government data sets.

Let’s say the year is 1986. A 6-year-old child has just been referred to your practice from the local school for an evaluation. You are using DSM-III to diagnose the child whose birth cohort is 1980. The next year, 1987, another 6-year-old is referred. This year, you are using DSM-III-R. His birth year is 1981. What does Deisher claim happened between 1980 and 1981? That’s right— a change point (1980.9). A few years pass and it is mid-1993 (to correspond more closely to the range of DSM-IV printing). Let’s call it 1993.5. Another 6-year-old, another DSM-III-R diagnosis for a birth year of 1987.5. One year later, in mid-1994, a new copy of DSM-IV hits your desk. Yet another 6-year-old comes in. Birth year 1988.5. Look at that! Another correlation to a Deisher change point, 1988.4.

Do I, personally, think any of this is valid? No, absolutely not. True study of autism epidemiology is far more complicated than this. Still, by following Deisher’s own model, the data clearly contradict her assertions and conclusions that DSM diagnostic changes do not correlate to her calculated change points.

Summary:

– Change points are artifacts of poor statistical approach (i.e. they aren’t real)

– Even if the change points were real, they do not correlate to introduction of changes in exposure to fetal cell line vaccines.

– If the change points were real, they do, contrary to Deisher’s claims, correlate to changes in diagnostic criteria between DSM editions.

Therefore, the central premise of Deisher’s argument (changes in autistic disorder diagnoses correlate with fetal cell line vaccines and not other factors) is not supported by this study.

If you’re still with me, congratulations! It may take a while to digest all of this, especially if I don’t get around quickly to putting up additional visual aids immediately. But if you think that there can’t possibly be more… oh, how wrong you are! I’ve barely begun my criticisms of this study.

Stay tuned for criticism of the biological plausibility and synthesis of Deisher’s conclusions…

See the other posts on this study [updated 9/23/14]:

– Abortion, Autism and Immunization: The Danger of the Plausible Sounding Lie

– Looking a little closer at the numbers— A supplement to Part I

– Problems with Deisher’s study— Part II: Biological Implausibility

* Note: If you are following along in this study and see other factors that I am neglecting to mention here, it is because they are red herrings that mislead and distract from that which is relevant. I will explain in detail later why these data are not relevant [updated]:

– Data outside the United States

– Paternal age

– Poliovax

– Havrix (Hepatitis A vaccine) & Pentacel

– Vaccine uptake for Varicella and Hepatitis A

[…] A later post post will address the merits of the “rogue fetal DNA causes autism and other harm” argument on its own merits. We want to give as fair treatment to the central thesis being promoted as we can, and that requires more time and outside consultation than was possible in a short time frame. […]

LikeLike

[…] to delve deeper into the problems with Dr. Deisher’s statistical analysis. In my opinion, Part I would have been far too long, especially for those with little/no exposure to statistics, if I had […]

LikeLike

Refuting the Rational Catholic by a rational Protestant

Claim: “…Other than the licensing of MeruvacII and MMRII, those other two things did not happen prior to the “change points”? In other words, the slope had already started changing before the vaccine exposure changes so the vaccines could not be the cause of the change.” -5th page

Refute: Because the change point graphs are based on birth year, and because the children are first exposed at 12-15 months, the change point on the graph will be retroactive to the exposure.

Claim: “…the Varicalla vaccine, Varivax, while licensed in March 1995, was not universally introduced to the vaccine schedule until 1996. Therefore, a change point of 1995.6 also would not correspond to Varivax because changes were occurring prior to the recommendation that all children get the vaccine.”

Refute: See above.

Claim: “While Deisher attempted to take the child’s age into account when looking at correlations between AD diagnoses and changes in diagnostic critera, she made no such attempt with vaccination.”

Refute: Age is accounted for by the U.S. vaccination schedule.

Claim: “The licensure of MMRII in 1979 would mean that any child 15 months of age at that time could use MMRII to satisfy his measles vaccine requirement. The first birth year that this would affect in full in 1978. “

Refute: Yes, it was licensed in 1979, but this is a change of vaccine, not introduction of a new vaccine. Doctors, clinics, etc. would have had a supply already of non-fetal vaccines which they would presumably use up before switching to MMRII.

Claim: “The 1989 recommendation for a 2-dose MMR schedule is a bit tricky; from 1989 to 1997, the second dose could be administered at 4-to-6-years-old or 11-to-12-years-old. The earliest birth year that this recommendation would affect is 1978 (12 years-old in 1990…)…The latest birth year would be 1986 (4-years-old in 1990).” -5th & 6th page

Refute: Look closely at Deisher’s graph B. There were jumps in 1978 and 1986, high deviations from the line, but not enough to constitute a major change point: There was a “triple whammy” in this time period: (1) the addition of a second dose of MMRII at ages discussed above; (2) a compliance campaign for the first dose of MMRII which brought coverage from 50% to 82% during the years 1987-1989 (this could have been administered to ages 15 months and upward, and (3) introduction of fetal-contaminated Poliovax in 1987, administered at 2,4,and 6 months. These multiple factors, administered at multiple ages, do indeed give more complex results, but as we can see, the rate of autism, sadly, did continue to climb during all these events.

LikeLike

[…] study: – Abortion, Autism and Immunization: The Danger of the Plausible Sounding Lie – Problems with Deisher’s study— Part I: The numbers – Looking a little closer at the numbers— A supplement to Part […]

LikeLike

[…] There are some fatally flawed published studies, for example, Dr. Hooker’s retracted study, or Dr. Theresa Deisher’s problematic work (also discussed here, here, and […]

LikeLike

[…] of dubious merit. Her theory is not plausible with what we understand about autism, her statistical analysis does not hold up to scrutiny, and her hypothesis is biologically implausible. We do not deny Dr. […]

LikeLike